a family tradition of nurturing naturally

about us

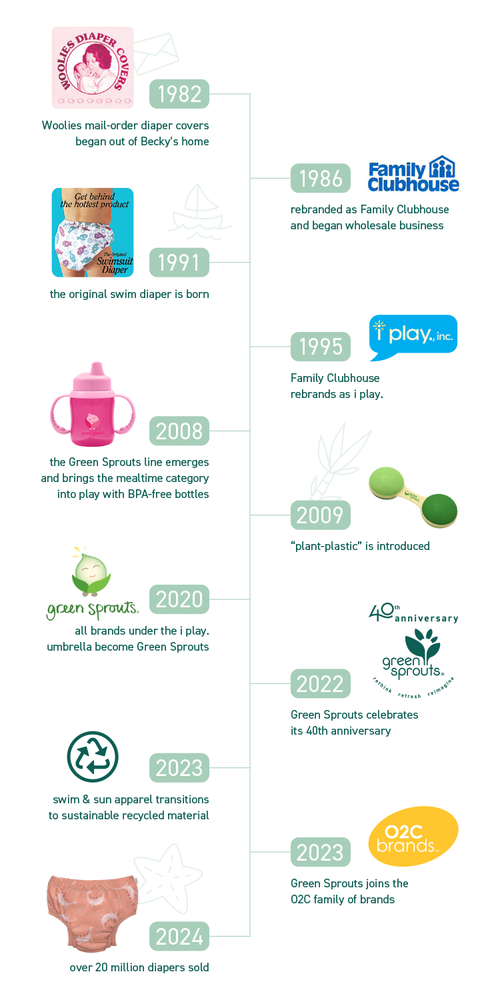

Founded in 1982 by a devoted mother of two young girls, Green Sprouts has been a pioneer in promoting babies’ health and environmental sustainability. From our humble beginnings as a mail-order company offering organic, eco-friendly baby goods, our commitment to babies' well-being has remained steadfast for over 40 years. Today, we proudly offer a full range of everyday baby essentials, designed to nurture the natural health of the whole child.

Today, our product categories span Swim & Sun, Mealtime, Daily Care, & Mindful Play. Our Swim & Sun line ensures head-to-toe comfort and protection with UPF 50+ hats, swimsuits, sun wear, and our award-winning Original Swim Diaper, boasting a patented triple-layer design. Mealtime and Daily Care selections prioritize pure materials to safeguard both little ones and our planet. Meanwhile, Mindful Play introduces toys crafted to foster developmental growth, engaging tots with sensory stimulation and holistic learning experiences.

grow healthy. grow happy.

natural products for the whole baby.

trusted by the experts, loved by all

The Original Swim Diaper

The Original Swim Diaper with a 40-year track record & continuous improvement. Our swim diaper has evolved since its development, but our commitment to babies' well-being has remained steadfast. Our patented triple-layer design is breathable, absorbent, and waterproof, providing both function and comfort for your little one. Trusted by swim schools and private swim instructors nationwide.

green sprouts through the years

As our founder, a devoted mother of two, brought her second child into the world she was struck by the need for products made with the baby in mind, setting the stage for 40 years of innovative product development driven by sustainability.